A Conversation with Ex-Google Employee Emaan Haseem, Fired For Palestine Advocacy

Emaan Haseem is an organizer with No Tech for Apartheid and a former Google employee. She is one of the people Google fired in April after NoTA’s bicoastal sit-in at the New York and Sunnyvale offices, including the office of Thomas Kurian, one of the executives leading Google’s genocide-enabling projects. Since leaving Google, Haseem has continued to organize for Palestinian liberation and has aided student organizing efforts, such as the encampment this past spring at the University of Washington. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you become involved with No Tech for Apartheid? What drove you to join the movement?

I officially joined No Tech for Apartheid last year in November, shortly after the escalation of the genocide in Gaza.

When I first got to Google, I looked up Project Nimbus in our internal search and virtually nothing came up. The one thing that did come up, though, was a resignation letter from Ariel Koren, a leading NoTA organizer in the campaign against Project Nimbus. Her letter was about how she had been pushed out of Google and given the “decision” to relocate in two weeks to Brazil as a result of her organizing efforts.

I was initially scared to speak out about Project Nimbus. But after last October, I had enough. There had already been base work done, so I dug around and found a way to connect with NoTA through the Alphabet Workers Union.

Were there any workplace policies or norms around free speech, particularly speech about Palestine? Did you face many bureaucratic roadblocks while organizing at Google?

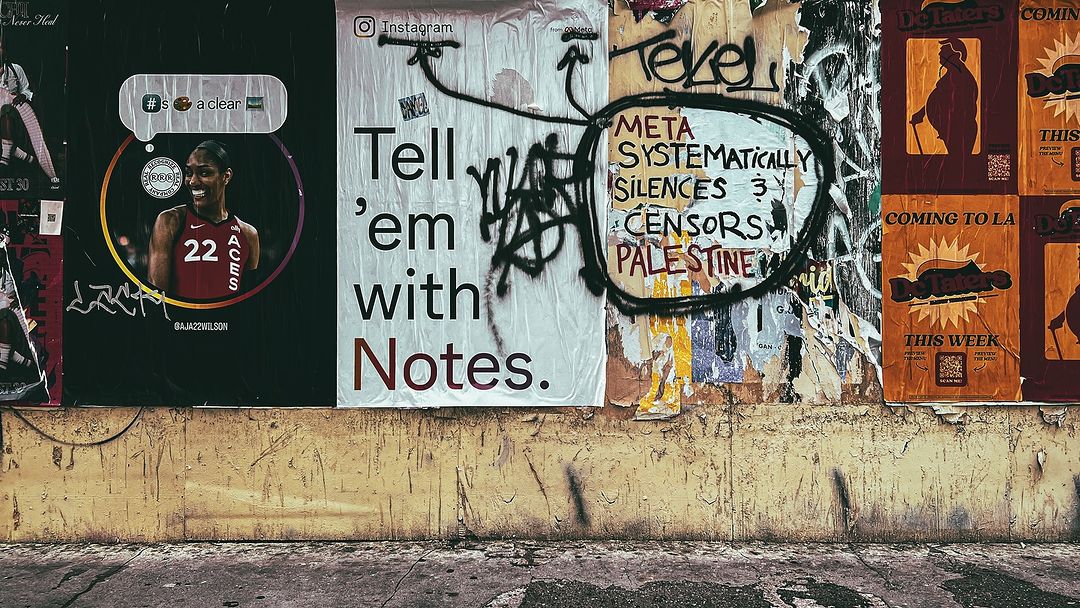

What we did see was an obvious and disproportionate use of “policies,” or really the very vague community guidelines Google weaponized to silence and repress us. If we posted an image of a candle to the company-wide forum and asked for a moment of silence for Mai Ubeid, a Google for Startups intern who was martyred in Gaza, the post was taken down. If we tried to say anything in line with a moment of silence, listed the death count, or posted “stand with Palestine” or “stand with Gaza,” those posts were taken down. Posts that read “stand with Israel” were left up, and I think they’re still up to this day.

What were the asks of the sit-in?

The first one was to end Project Nimbus, and all complicit contracts with the Israeli government. The second one was to protect Arab, Palestinian, Muslim, and allied voices from repression, silencing, and retaliation. The third one was to recognize that Project Nimbus contributes to a worker health and safety concern. There were people who, even before the sit in, ended up leaving the company because they just couldn’t take it anymore. It’s terrible to be in a place like that while you’re witnessing images that you are, paired with the dissonance of the retaliation.

And then you all were there for a while, right?

The sit-in went on for nine hours. I left early and helped facilitate a rally outside. And on the inside, they were dealing with all sorts of crazy things: Security was stopping them from using the restroom and receiving food and water.

What did the days following look like? Were you fired soon after?

We all had the idea that an investigation was coming because they said there would be an investigation. But then, surprisingly, they just ended up firing everybody who had been taken off of corporate access. There was no investigation. No one was contacted; everything was automated through a bot. That was surprising to me, because I really didn’t think Google would be so sloppy about it — it is very sloppy to fire what ended up being 50 people without an investigation.

There were people fired who weren’t even participating in the sit-in, but just people who had walked by, were curious, and had questions. In fact, most of the people fired had not been participating in the sit-in.

What’s really interesting is that for a lot of these people, this was the first action they had ever witnessed or attended for Palestine. And for many of them, it was a point of radicalization. People were shocked, and saying things like: ‘Wow, Google doesn’t even look at us like we’re human. It was just a click of a button for them to fire us.’

How would you respond to critics of NoTA, who believe that Google employees not directly involved with Project Nimbus are not responsible for it?

People definitely like to raise this abstraction, which has been upheld by the lies Google has touted. Google tries to deny as much as they can, including Project Nimbus’ clear ties to the Israeli Occupation Forces, in order to maintain the calm of their employees. This calm isn’t really calm, but repression.

All tax-paying citizens of the United States are contributing to the genocide in Gaza monetarily. I think we need to look at those of us who work for mega corporations providing the tools for this genocide the same way. While not everyone may have the means to get fired, we would be remiss to lose the opportunity to organize internal worker power and to pressure executives to drop contracts [with Israel].

On all fronts, we need to make clear that genocide is unprofitable, and that if companies institutions try to profit off of genocide, it won’t happen easily. They have to be on their toes. They have to be scared. They have to be looking over their shoulders.

What can we, as non-Google employees, do to help? Should we boycott Google? What does that look like?

The average consumer should try their best to boycott these products. I know it can be hard, but it’s possible to start by boycotting Google Search and using alternatives instead, like DuckDuckGo. Google search is one way that Google boosts a lot of their ads, which I think is their most profitable sector.

What would you tell people — say Harvard seniors — applying for jobs at Google or elsewhere in big tech?

For students looking to apply to big tech, I can’t necessarily tell people not to do that entirely, but do try to avoid applying to these companies. They try to pull people in with their benefits, but I think it’s important to know that a lot of these benefits, especially from places like Google, are not really necessary or worth evaluating if you’re weighing genocide in the mix.

I think we should be in the struggle to imagine a world where we don’t have to depend on these companies complicit in genocide. I don’t imagine this to look like a one and done startup; I think it requires a revolutionary framework and a lot of education. We do have the potential to grow and build this world, and it definitely starts with the struggle to imagine what we can do better.